I think I got the best of both of them.

“Dad, Gio is the best player here by far”, Jack said to Claudio while watching his younger brother trying out his basketball skills for a local team.

“He wasn’t jealous about anything”, the father will later remember. “He absolutely thought Gio was incredible.”

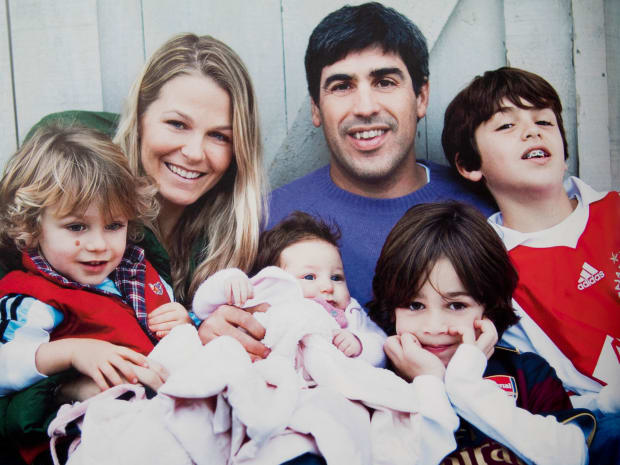

Just a few months later, barely 13-year-old Jack Reyna would die of brain cancer leaving his nine-year-old brother Giovanni as the oldest of – from then on – three children of former United States international footballers Danielle Egan Reyna and Claudio Reyna.

The evening after his older brother died, Gio reportedly told his mother that he was never going to be a good soccer player now. He felt it was Jack, and not any of the parents, who had taught him everything.

Giovanni has recently got himself a tattoo on his right arm. It reads: Love Jack.

BASKETBALL LOVER

Giovanni Reyna was born in November 2002 in north-east England when his father Claudio – the first American to captain a European football club while on loan at Wolfsburg from Bayer Leverkusen in late 1990s and then U.S. Men’s National Soccer Team skipper at the 2006 World Cup – was playing for Sunderland.

Just over four years later, via a three-and-a-half-year stint at Manchester City, the family moved back across the big pond where Reyna senior saw out his playing days at New York Red Bulls.

Meanwhile, his second son quickly started to show his own footballing potential.

“He used to dominate U9s soccer in the park, when he was five“, Claudio recalled of little Gio‘s first steps with the ball at his feet.

In a country that seems to strongly believe in late specialisation, however, it was not until Giovanni was nine years of age himself when he joined his first football club. He would stay at New York Soccer Club for two years before moving to New York City FC.

As a kid, he would play different sports, including American football and tennis.

His favourite one, alongside football and similar to Lautaro Martinez, was basketball.

“In the end, it was always going to be football, but I also played really competitive basketball in New York City until I was 12 or 13″, young Reyna has revealed.

“After that, I had to stop, as this was obviously my priority, my main option, and my passion.

“I really love basketball though, and still follow it now. I try to watch as many games as I can […] Basketball, besides soccer, is my next love.”

BLEND OF PARENTS

If Giovanni Reyna indeed has football in his blood, it is not down just to his father.

His mother, Danielle Egan Reyna, also played football professionally and even made six apperances – all starts – for the U.S. Women’s National Soccer Team back in 1993. They were world champions at the time.

Her supremely talented son could be regarded as a blend of his parents’ footballing abilities.

“I think my parents say I got the best of both of them, to be honest, because my dad was more of a technical, combining player, good on the ball, and with good technique, while my mum was more of a runner“, Gio has said himself.

“I think I can run pretty well too, but I also have a good technique and a good combination.

“I think I got the best of both of them, but I can still always work and improve on both of them.”

As with Lilian Thuram and perhaps contrary to common expectations, neither Danielle nor Claudio seem to have ever put any pressure on any of their children to pursue a sporting and let alone football career.

“They try to keep me grounded, obviously, because there is a lot coming at me right now”, Giovanni admitted at the start of this calendar year.

“I know that though, and not only them, but a lot of other people tell me that. It’s still a long way to go, and I know there’s still a lot of work.

“They obviously say they’re proud of me and they love what I’m doing over here.”

Claudio Reyna claims he never really played football with Gio even in the family garden.

This was Jack’s domain.

In the picture: the Reyna family before the death of Jack, Giovanni is wearing an Arsenal shirt (found here)