No one was able to take the ball off him.

Bori Fati must have been surprised, if not worried.

When returning home from work, like every day, he encountered a group of neighbours and young boys waiting for him on the doorstep.

“Do you know what you’ve got here?”, he was asked. “You need to see it. This kid needs to play at a club.”

The kid has not stopped since, his dad himself has admitted.

DECADE OF GRAFT

Everyone has their own unique story. The one belonging to Bori Fati appears simply exceptional, though.

The Bissau-Guinean was a semi-professional footballer in his homeland until his wife, María, got pregnant with the couple’s first son.

The father quickly made a life-changing decision. He opted to travel the world in the search of a better future for his family.

He first spent four years working in Portugal before heading to Andalusia, where he helped with the construction of the railway line between Córdoba and Málaga. It was then when he moved in to the village of Herrera. He still lives there today.

Upon completion of the railway works, Fati senior reportedly offered his services for a variety of job roles: from a bricklayer, through a waiter, to a dustman.

He was a likeable character. As a result, he received help. Including from Juan Manuel Sánchez Gordillo – the mayor of Marinaleda, another village just west of Herrera. Bori became the politician’s chauffeur.

It was only then, a decade after first setting foot on European soil, when he could finally afford to bring his family over from Africa.

His second son, Anssumane, was six at the time.

TIME CONSTRAINTS

Despite his footballing past, the father was simply too busy to even know about Ansu’s own love for the game.

“I did not even know he had played [football] in Guinea”, he revealed. “I presumed he had kicked the ball around in the street, but nothing more.

“He told me he wanted to play and [asked me] to take him to the pitch, but when I managed to bring the family [to Spain], I had a lot of things to do and I did not have the time.”

Young Ansu – along with his 11-year-old brother Braima – had to take the matter into his own hands.

BAREFOOT

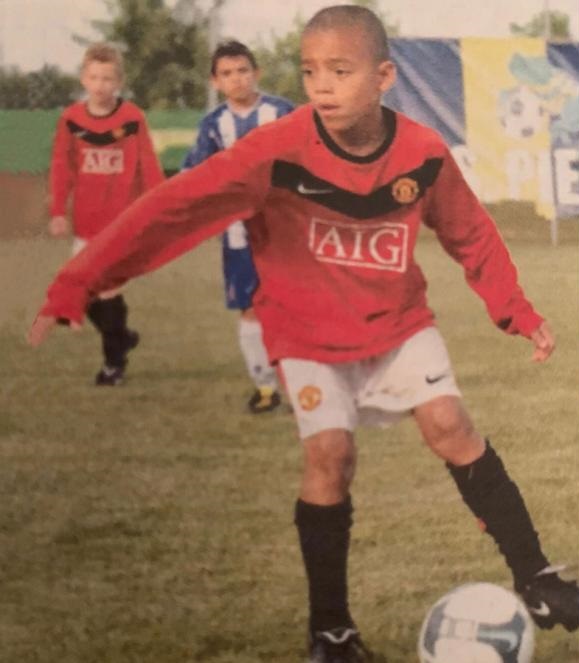

It was at the end of the summer, back in 2009.

According to Joaquín Sánchez, the six-year-old, who first turned up to a training session in his new home, was quite tall for his age and very slim.

He was also barefoot and wore swimming trunks. Not that it bothered him.

“He was spectacular, we were left astonished”, remembered the local club’s head of coaching. “We did not know where he had come from, but it was clear he could play: no one was able to take the ball off him.”

Sánchez was even more amazed when Ansu answered his following two questions.

“Who are you with?”

“Where do you live?”

PASSION

Of course, young Fati – who also has one younger brother and two sisters – did not stay long in Herrera.

He was soon spotted at a tournament by Pablo Blanco, head of academy at Sevilla, who brought him to the club.

A year later, both Albert Puig of Barcelona and Paco de Gracia of Real Madrid paid visits to the family.

“Madrid offered me better conditions in terms of money, a house, everything”, Bori Fati recalled. “But I chose Barça because Valdebebas [Real Madrid’s training ground] did not have a hall of residence at the time and I did not want the young boy to get lost [in the city].”

As remarkable as it sounds, the just nine-year-old Ansu was on the move again. This time he was to live among strangers, at the famous La Masía, although his older brother was taken up by Barcelona, too. Initially, his mother also managed to spent several months in the city.

“It was very difficult for him”, Jordi Figueroa, Fati’s coach in Herrera, remembered. “If Ansu is where he is now it is because, above all, he likes football. He has an incredible passion [to the game].”

Bori Fati can probably still scarcely believe his luck.

In the picture: young Ansu Fati could have joined Real Madrid had the club had a hall of residence at their training ground at the time. Last week, as a Barcelona player, he scored his first goal for Spain at Valdebebas (found here)